The human tendency to be right-handed or left-handed boggles scientists. Other animals, even other primates, tend to be less lopsided. This distinctly human anomaly has generated a fair share of pop-science folklore—that left-handers are more creative, for instance.

But handedness has no influence on personality traits, according to psychologist Daniel Casasanto of the University of Chicago. It does, however, influence bias. His work has shown that right-handed and left-handed people have preferences not only for which hand they use to write, but for which side they mentally associate with positive qualities like intelligence and honesty.

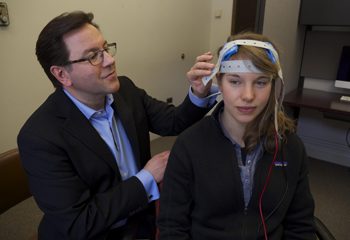

Since scientists estimate that righties make up to 90 percent of the population, Casasanto’s studies have uncovered a society mentally biased toward the right. Most politicians reserve their left hand for negative gestures, and most parents prefer baby names typed on the right side of the keyboard. Now, Casasanto is studying how handedness affects “approach motivation”—how we approach or avoid physical and social situations in the world around us.

Casasanto discussed his work at the February 2016 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Washington, D.C. Afterward, he helped SciCom’s Natalie Jacewicz get a handle on society’s rightie bias, and what that means for lefties.

____________________

Editor's note: The Atlantic has published the full conversation between Natalie Jacewicz and Daniel Casasanto.