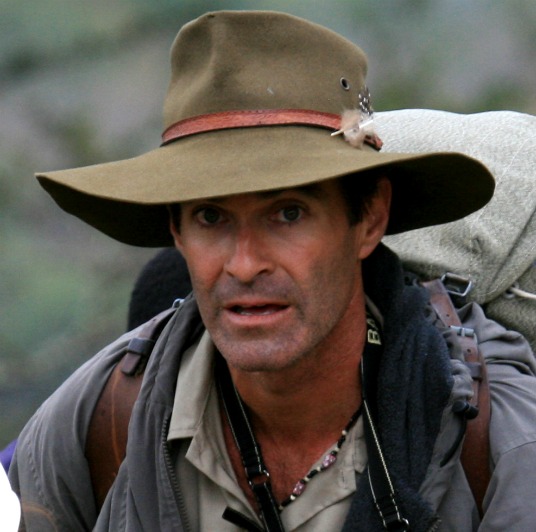

Jay Vavra teaches science for the real world. His eleventh graders take their classroom lessons and apply them to problems like wildlife conservation. They've mastered DNA analysis and taught Tanzanian officials how to genetically identify bushmeat, illegally poached wild animal meat from the African forest. They've waded through San Diego Bay, observing its beautiful wildlife and industry, and published books about the ecosystem and its problems.

Vavra has been exploring nature around the globe since he was 6, and he now inspires his students to study science and travel. Since earning his Ph.D. in marine biology from the University of Southern California, he has promoted science literacy through programs such as Roots & Shoots, a global service learning program created by celebrated primatologist and friend Jane Goodall. He collaborates with local biotech companies to procure funding and internship opportunities for his students and has won numerous awards for his teaching.

Vavra inspires other teachers to try inquiry-based learning projects through conference talks, like the one he gave in February at the 2010 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in San Diego. Teachers practically jumped out of their seats at the end of his talk, wanting to know how they might apply his techniques. Vavra acknowledges that San Diego's High Tech High is no ordinary high school, but he says his methods can be used in other programs, even those with limited resources.

When he's not in the classroom or in the field with his students, Vavra often explores San Diego Bay with his wife and two young sons in their skiff. SciCom's Gwyneth Dickey caught up with him for a conversation.

Who inspired you to love science?

My early mentor was a family friend named Richard Lantz. We used to take trips to Baja, and whenever we were exploring—down in the tidepools or fishing—he knew everything about the animals and plants that we'd see. He inspired me through his passion and the wealth of things that he could tell me.

So you have a love of travel. Is that something you try to instill in your students?

I want my students to know the world. You don't really know yourself until you know the world around you. You get an understanding of how to treat others and what we have and don't have. There are so many benefits to travel, but it's tough recognizing that if you don't have those opportunities.

What was it like to bring students to Tanzania?

It was a dream. Since working there on a book with my uncle, called Remembering Africa, for which I photographed and documented wildlife, I always dreamed of going back, especially with students.

But we had a horrific beginning. The very first day, as we were leaving the city of Arusha, our safari truck accidentally went off the road and turned over. Because there were no seatbelts, I instantly feared that maybe somebody had lost a limb or even a life. But everyone was fine and the event united us all instantaneously. There was discussion among the parents of perhaps going back home immediately, but the students protested. It really showed their commitment to the whole project.

The bushmeat topic is kind of gory. How do students react to being in a country where poachers kill animals?

Supposedly, poached meat has become the new blood diamond, involving large organized groups with lots of money and guns. There was some worry that if we publicized our expedition too much it would put us in danger. But as I expected, we found incredible support once people realized what we were up to. The fact that people truly appreciated our work and wanted to support us really empowered the students. Not only were they experiencing one of the most beautiful places in the world, but at the same time they were actively doing something beneficial for biodiversity and for Africa.

We tried to convince people that there's much more value to the live animal than the dead animal. We made the case that the cost per pound in the meat market is nothing compared to the tourist dollars they bring in, if you can save these species. The bushmeat crisis is incredibly complicated so it seems daunting to solve, but at the same time there are so many ways that students can learn from the whole issue.

"Every day I ask myself, 'What would Jane [Goodall] do?' She has this message of hope that I always try to instill in my students."

You've worked closely with Jane Goodall. How she has influenced your teaching?

Every day I ask myself, "What would Jane do?" She has this message of hope that I always try to instill in my students. Her ability to take a situation, no matter how tragic or difficult, and show that there's the potential to turn things around and improve the world is beyond inspiring. I always tell my students that someone her age, instead of having this gloom-and-doom outlook and dwelling on the idea that the past was so much better, still has hope after seeing so much destruction.

Why is High Tech High a good place to study science?

It's their whole philosophy—using project-based learning and innovation. They're trying to develop students who are real problem solvers, rather than just ones that gain knowledge. Previously I was at a school where everything had to be aligned with [testing] standards. At High Tech High, they want us to teach topics in depth so we can really hook students.

Are High Tech High Students especially excited about science?

Maybe not more than at any other school. But one thing we hope is that students question more and try to discover new things rather than just memorize information. Our whole culture is based on solving problems. Students collaborate with each other and become quite comfortable interacting with outside professionals. We hear that when the students go on to college, they easily go up and talk to their professors, and they're more comfortable finding others to help them.

What's the major difference between your curriculum now, and when you started at HTH?

It's more freeform now. I almost allow the experiment to drive the curriculum, and I may not be sure what I'm going to teach the next week or even the next day. Some of it is truly driven by the experimental results we're getting. In a way, the school is kind of like a graduate school. It's based on how the project is going, rather than the syllabus. I guess you could say it's a very organic syllabus.

So do you have a set curriculum?

The San Diego Bay project has been a foundation. Each year we address different aspects of the bay from an urban ecology perspective—everything from describing the animals to looking at their interactions to thinking about how we can learn from them to make new products or systems. We also take an invasive species approach—what are the impacts on the ecosystem from abroad? Every year the bay is a starting point, but we've found so many different interesting topics that relate to it.

What unique contributions have your students made to the study of San Diego Bay?

In their books, the students have portrayed the beauty of the bay and its wildlife as well as its problems. It's a beautiful place, but at the same time there's industry and ugliness there. They've inspired people to do science in their own backyards and discover what's in their community. In describing their community, they get to know it, and in turn they get to know themselves a little better.

What are scientists' impressions of literature from high school students?

I've heard people question it because it comes from high school students. One person even told me that high school students at this age can't synthesize such complex information and put together an accurate story. But I really differ. I've worked with a lot of science fair students and they're doing real science, telling a story from beginning to end. They need a lot of coaching and a lot of help, but they can do it. Our books actually go out for scientific review. That's real science.

How do you think your classes could improve?

It's important to always keep changing. I feel that in areas where I don't create new material, I don't find it interesting and neither do the students. So I always try to make the lessons as original as possible. If it gets stagnant, even if it's a great lesson, I'll get bored and students can pick up on that.

Do you incorporate other subjects into your science studies?

On a single project, we may integrate biology, math, humanities, graphic arts, and multimedia. That's something that happens in the real world, for instance, when different companies come together to work on a single product. At High Tech High teachers are willing to be flexible and see new ways to solve the problem. That carries over into the student population.

I'm curious about what proportion of your students go on to study science in college.

I'm not sure about the numbers, but I do have a fair number come back and tell me what they're up to. I was visited recently by a former student who graduated from Bryn Mawr and did a medical internship in Swaziland. She is now working in a cancer lab for NIH [the U.S. National Institutes of Health]. She's an African American female student from a single parent family. I was low on energy the day she came by my class, and her visit really raised my spirits.

How can your teaching can be applied to programs without much funding?

The key is a lot of collaboration. There aren't many scientists that do it alone; they seek others to assist them. If scientists find you share their interest and you have the energy for it, they'll come to your aid. If your intentions are good and you have the background and the willingness, others will help you find your way.

What would you say to a teacher who wanted to try it for the first time?

Start small and choose a project that interests you, perhaps where there's some need in the community or the environment. A lot of young professors step into a college and there's no funding, so they've just got to scrape away. You do the project to the best of your ability and go step by step. It's just like starting a small business; there's a lot of entrepreneurship mixed in.

How does your work fit in with other efforts to promote science literacy?

I think these [San Diego Bay] books redefine science literacy. It's not just teaching students how to interpret science, but they're actually interpreting their own science for the world. That's the ultimate goal—to get them to conduct good research, analyze it appropriately, and then put it into a language that anyone can understand.

Gwyneth Dickey, a graduate student in the Science Communication Program at UC Santa Cruz, earned her bachelor's degrees in neurobiology, physiology, and music performance and her master's degree in kinesiology, all from the University of Maryland. Her school-year internships have included the Monterey County Herald, KUSP-FM in Santa Cruz, and the Stanford University News Office. This summer, she will work in Washington, D.C. as a science writing intern at Science News.

© 2010 Gwyneth Dickey