“Come on, Jeremy, we’re supposed to be positive!” Those were the pleading words of a colleague of Jeremy Jackson, a coral-reef ecologist who spoke at the 2009 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Chicago. Jackson meant to talk about successful fishery stories in the Pacific Ocean, but he quickly digressed into his usual dirge about the decline of global marine ecosystems.

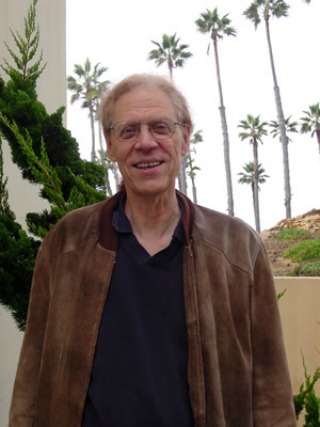

Jackson, from the Scripps Institute of Oceanography, can’t help himself. He’s made passionate pleas about the dire state of the world’s oceans since he published a 2001 paper in Science on the collapse of coastal ecosystems.

His latest paper, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shows things are only getting worse. Jackson foresees the future marine ecosystem as a “brave new ocean,” where clear and productive coastal seas turn into oxygen-starved dead zones, and thriving food webs degrade to seas of slime and disease.

Jackson discussed this vision in Chicago, but he also spoke at an enlightening symposium organized with his wife, Nancy Knowlton of the Smithsonian Institution, called “Beyond Obituaries: Success Stories in the Ocean.” He showed that Pacific coral reefs protected from pollution and fishing are more resistant to climate change. Other speakers claimed that some New England fisheries can recover within a decade when fishing is halted, and that conservation is possible when communities and countries work together to manage common resources.

During a press briefing for the symposium, Jackson quickly strayed from the bright side. Afterward, he provided insight into his pessimism—and offered reason for hope.

How have you seen the ocean change in your lifetime?

I first went to Jamaica as an enthusiastic Ph.D. student in 1968. Jamaica had the most beautiful coral reefs I had ever seen or have seen since, with 50 to 80 percent living coral. I’d take my son snorkeling even in 1979, and the reefs were still beautiful. I could take him out to 100 feet, worrying about him like mad, but because of the transparency you could see all the way to the bottom.

Then in the mid 1990s, the reefs of Jamaica were reduced to 5 percent of living coral and the water was really dirty. You couldn’t see the bottom in water deeper than 30 feet. Discovery Bay Jamaica was a place I must have dived 3000 times. I can still close my eyes and see what it looked like. It was all gone.

What caused these drastic changes?

Coral reef ecologists get in embarrassingly silly arguments over what are the most important causes of coral mortality. Is it overgrowth of seaweed because of fishing, or is it climate change and bleaching, or is it disease and organic pollution? The way I like to answer the question is “yes,” it’s all of these things.

"I turn on the audience and say, 'Is this going to be another one of those talks where you all clap your hands and say, "Oh Jeremy, you're so wonderful," and then you drive home in your SUV and don't do anything?' You can see people squirm."

Your first talk was based on your Brave New Oceans lecture series. Tell me a little bit about it.

Doom and gloom is very much a part of the lecture series. In Chicago, I rushed through the grim news and spent a little more time on research needs. But it’s obvious that I am a little cynical about research needs as opposed to political reality. What I do more now when I am in a public lecture and don’t have a ton of press around is talk about citizenship. I talk about how the only way any of this is going to change is if you, the audience, care.

What do you hope people will take away from your lectures?

When that Science paper first came out, it got attacked all over the place. People said oh no, it’s not all that bad. So my primary goal was just to get people to realize we are the problem. That went for scientists as much as the general public. In fact, the ultimate irony is that scientists have been the worst foot draggers. The public gets it, at least the public that will come to a lecture about the oceans.

I looked up a couple of student blogs to see how people were responding to your Brave New Oceans series. Some people walked away feeling devastated and hopeless.

I know that, and that’s one of the reasons I stopped writing my book. I started a book five years ago about all of this. I wrote like mad, but I finally realized it was going to be just another obituary of nature and so I stopped.

When I give my talk, I like to start with Rachel Carson and Silent Spring. If you deconstruct Silent Spring, the whole book is nothing but three questions: What’s going on that’s new, different, and scary? What’ll happen if we don’t fix it? How can we fix it? I realized that I was answering the first two questions, but not the third. Not only that, I didn’t know how to answer the third one.

That’s the hard part.

Yes, that’s the hard part. It’s easy to be a scientist and hard to be, shall we say, an ethical politician. So I started telling people that we have to take the situation seriously and really think about your role as citizens.

You mean people taking personal responsibility?

Yes. I gave the talk two weeks ago at the University of Wisconsin, Madison and UCLA. And in both of those talks, I switched into this mode I would never have had the guts to do two years ago. I turn on the audience and say, “Is this going to be another one of those talks where you all clap your hands at the end and say ‘Oh Jeremy Jackson, you’re so wonderful,’ and then you go have a glass of wine and drive home in your SUV and don’t do anything?"

You actually said that?

Yeah, I did say that in my talk at UCLA. You could see people squirm. And I said I know what I'm talking about, I looked out in the parking lot and saw that half the cars were SUVs. And so, then I do my shtick about citizenship. I tell them to find out what your senators and representatives believe. Change the way you live, because if we are going to avoid these disaster scenarios, then we are going to have to start driving hybrids or better yet, take the bus.

Do you think they walk away from it and change their behavior or think differently?

Well, that’s the 64-dollar question. When I first started giving the talks, I didn’t care whether they changed their behavior as much as I cared about them just saying, ‘Oh my god, this is bad.’

Tell me more about the “Beyond Obituaries” symposium you and your wife organized at AAAS.

Nancy came back from AAAS the year before and told me there were 21 marine science symposia with nothing but doom and gloom. It was such a turn-off to her. We decided the time has come to strike and to do this beyond obituaries thing. We still need to tell the truth, but should people go away thinking there is nothing I can do? Or is there hope? And that’s why we did it.

It seems you’ve had a bit of change of heart with this new symposium.

It’s not a change of heart, it’s a strategy. Who the hell would care if we hadn’t pounded into them that the news is terrible? It was a big risk Nancy and I took to do a success stories thing because people ask, what’s the news? Nancy started off the press conference by saying that the good news never leads. People only write about the bad news, but doctors don’t just write obituaries of their living patients. The symposium worked, and we’re going to do it again.

Are you hopeful we can take these success stories and learn from them?

We both feel you have to be realistic, but you also have to have reason to hope. Ultimately, I wouldn’t be giving these talks if I didn’t have hope. Now my view of what the future is going to look like would be deeply depressing to most people because I am a scientist. I study this stuff so I see the reality of what’s happening, and it’s not a pretty picture. But if we tax the hell out of energy use and get a little bit smarter about the hog and chicken industry—which is just a crime—things might get better.

So are you really hopeful that people can change and that the system as a whole will change?

I think it’s going to take some catastrophes. I think President Obama gets it, and I think his inner circle gets it. I think they are doing enormously important things and working hard to move the center of the country subtly to the left toward a greater environmental awareness.

If you could implement one thing today, what would you put into place immediately?

As a quick thing that requires no technology, we should tax the hell out of energy use across the board. That one thing would be revolutionary. It would mean that trawling would become uneconomical. It would mean that going out to the middle of the ocean to catch fish would become uneconomical. It would mean using excess fertilizer made from natural gas, an enormous energy expense, would become uneconomical. It would mean that the manufacturing of a lot of things that are toxic would decrease, because it would become uneconomical. And it would mean less CO2 in the atmosphere. Isn’t it amazing that one thing, and one thing only, would change the world?

Cassandra Brooks, a graduate student in the Science Communication Program at UC Santa Cruz, earned a B.S. in biology from Bates College and an M.S. in marine science from California State University/Moss Landing Marine Laboratories. She has worked as a reporting intern at the Santa Cruz Sentinel, the news office of Stanford University, and the news office of Stanford's Woods Institute for the Environment. She will work as a summer science writing intern at the news office of Children's Hospital Boston.

© 2009 Cassandra Brooks