Animal farming consumes about one-third of the planet’s land area. It may take much more to satisfy the world’s skyrocketing population. Recent studies suggest that meat and dairy production spews about 18 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. Balancing global food needs with environmental concerns may require a radical solution: synthetic sirloin.

Physiologist Mark Post of Maastricht University in the Netherlands is growing the world’s first in-vitro hamburger with stem cells from a sesame-seed-sized chunk of cow muscle. The cells multiply in a dish to form a taut tissue strip between two Velcro anchors. Under tension, budding cells make proteins that twitch the muscle, helping the proto-hamburger bulk up. A single hamburger requires 3,000 tiny strips, each of which takes six weeks to grow.

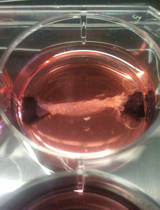

As yet, there’s no mistaking the petri dish creation for a dinner dish. The burger strips possess a yellowish-pinkish hue, which Post hopes to fix by adjusting the cells’ biochemistry. And without a mix of lab-grown fat cells thrown in, the protein-rich strips would feel like squid meat. Post plans to troubleshoot color, taste, and texture in the coming months.

The first proof-of-concept burger will cost 250,000 euros (about $330,000), paid for by Post’s anonymous financier—a “reputable source of money” without ties to the food industry. If that first hamburger hits the spot, Post hopes to secure funding to develop faster and more cost-efficient techniques.

Post spoke at the February 2012 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Vancouver, Canada. During and after the meeting, he chatted with SciCom’s Helen Shen about the technical and philosophical challenges of bringing lab-grown hamburgers to the table.

Have you eaten any of the meat yet?

No, I haven’t. I’m a scientist, so I need a reason to do something, and these strips take time to make. If I eat them, I eat an experiment. And that’s fine if I have a particular reason to do so, but right now the only reason I have to eat an experiment is to answer questions from journalists with a "Yes," which is not a good enough reason for me.

I read there was one journalist who had tried it?

Right, right. We had a crazy Russian colleague of yours, and he knew that we had grown a couple of strips for the purpose of this film shooting. He wanted a pair of tweezers—I didn’t know why—but he actually took the tweezers and plucked it out and stuffed it in his mouth. In the lab. Which is of course forbidden—you’re not allowed to eat in the lab. It was just a funny sort of episode. And he still lives.

"Taste is going to be an adventure. We don't know enough about the chemistry of the taste of meat."

So you have a single data point?

Yeah, of non-toxicity, yeah! But he confirmed that it doesn’t make sense to eat these small pieces because he couldn’t taste anything.

Why might the lab-grown hamburger taste differently?

Right, well… I think we all agree that fat is a huge component of the taste of meat, and this didn’t have any fat. Also when he gobbled this up, it was not matured yet. And of course, it was not cooked. But taste, that’s going to be an adventure.

We don’t, as scientists, know enough about the chemistry of the taste of meat. We are working under the assumption, which might be naïve, that if you take the right source of cells, and if you let them grow under conditions that are very similar to those in an animal, and you do the same with the fat cells, then they will re-create the taste of the original animal. Whether that’s true, we’ll find out.

Could you make a pre-seasoned hamburger? We do know some of the molecules involved in spicy tastes, for example.

Yeah, you could genetically engineer it, but I have steered away from that discussion because this is already a complex issue to the general public. Already you have to fight a Frankensteinish sort of feeling, so if I confuse this discussion with genetic engineering, that’s not going to help. That’s why I’m stressing, let’s first let the cells do their biochemistry, and see what the outcome is.

Would the success of a lab-grown hamburger mean that we could be free from using animals for meat?

No, but it means that we could use significantly less livestock for meat. That can go up to a factor of a million to maybe even a billion fewer animals. But, as I see it, with the current technology we would still need donor animals to supply the stem cells.

Why is that?

Well, because the particular stem cells [adult stem cells] we use have a limited life span, so they cannot divide forever. They will, at some point, stop dividing and then you would need occasionally to kill a donor for its stem cells. Or, take a biopsy from a new animal, let the animal live and take the stem cells from there.

Would this be different if you used embryonic stem cells?

Embryonic stem cells have been shown to replicate even further, but also there is a limit to that. You would just reduce the livestock even further, but you would keep a small number of animals—small, as in a couple of thousand—to avoid the danger of making them extinct.

A couple thousand animals could be sufficient for the world’s meat?

Theoretically, yes.

How does the environmental impact of making a lab-grown hamburger compare to producing a real one?

Um, we don’t know at the moment. Other people have done an analysis with quite a big number of assumptions. They figured out that in-vitro meat would reduce land usage by 99 percent, energy by about 40 percent, and water usage by about 90 percent. But there are a fair number of assumptions.

What reactions have you received from vegetarians?

Well, mixed. Some people say well, if you can reduce livestock that much and provide sufficient welfare for the animals, then I might start to eat meat again. Others say no way, it’s an animal-derived product. I’m not going to eat it. The real issue is not the vegetarians. They are a minority; they already eat in very environment- and animal-conscious ways. The challenge is to get the meat-eaters to start eating an alternative product that’s better for the environment and better for the animals.

Have you gotten any reactions from meat-eaters?

Yeah, of course. A lot. If you just asked around, “We’re going to get hamburgers out of a laboratory without a cow being used for it. Would you eat that?” Without any preparation, uninformed people—their first reaction will be “No.” My experience with the general public is that with a little bit of information about the crisis that we are going to face with meat production and the consequences of meat production for the environment, they will start to look very differently at that prospect.

Your first lab-grown hamburger is going to be one-of-a-kind and quite expensive. How soon do you think it could become affordable for the general public?

That’s pretty tough to answer. If we had unlimited resources for research, in terms of people and money, it would still be a major challenge. It would still probably be somewhere between 10 and 20 years.

After the hamburger, would you be able to make a steak by the same means?

Well, the principles are the same, but the technology would be slightly different. We’d need to create a system that allows thick pieces of tissue to grow outside of the body. For that you’d need an artificial blood vessel system and a flow system to get oxygen and nutrients into the center of the tissue. Those technologies have been implemented in biomedical tissue engineering. We haven’t done that yet for meat tissue engineering.

What about adapting these techniques across different meats?

Well, we moved from mouse to pig to cow, and that was pretty easy. Other people have done fish and chicken, and so I don’t suspect that there are going to be major obstacles doing this from any type of vertebrate animal.

What are some of the criticisms you’ve gotten about your approach?

Well, just after Vancouver, I got my first hate mail.

Wow.

Yeah, a guy basically wanted me dead. It was something like, “You’re going to take out the last type of natural food that we have, and transform it into something that’s completely technological and human-made.” Of course this is something real, and hopefully not many people will express it with the same venom.

And then there are other people who say well, you know, it’s just never going to happen. You cannot, you will not be able to make it efficient. You will never be able to make it cost-effective. You will never be able to make it look, feel, and taste exactly the same as meat. So there are lots of skeptics.

Would you be inclined to be a skeptic, if you weren’t working on the project yourself?

I would probably also look at it with a degree of wariness. I like meat, and I’m kind of a gourmet, so I like to cook as well. So I’m very sensitive to the argument that this used to be a natural thing, and if you go ahead, at some point, it will just be factory-made. I mean, you’re talking to a person that ten years ago still went to the farmer to get raw milk cheese. But since then I’ve learned that there is a real need for these alternatives, and that they could be a solution to a fair number of issues.

Do you eat hamburgers often? Do you like them?

Actually, no. I don’t eat them very often. My kids love them and they eat a lot of them, but it’s not my first choice meat product. From the grill, I actually prefer fish.

Have you thought about how the lab-grown burger would be labeled in the market?

Well, that’s not for me to say. That’s a regulatory thing, but we talked about this many, many times. We eventually just decided we should call it ‘meat’ and nothing else, because that’s what it is. It has the same composition, it’s from the same origin. The only difference is that it’s not grown in an animal, so why not call it meat?

I have students in food law using this as a case, and I would have to ask them whether they have reasons why you wouldn’t be allowed to call it meat. That really depends on whether you can protect meat as a product that necessarily needs to grow in an animal, and I don’t know what the legal definition of meat is. If there is such a thing.

_________________________

Helen Shen, a graduate student in the Science Communication Program at UC Santa Cruz, earned her bachelor's degree in biology from Stanford University and her Ph.D. in neuroscience from UC San Francisco. Her internships have spanned the Philadelphia Inquirer (AAAS Mass Media Fellowship), the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory news office, the San Jose Mercury News, and Nature. This summer, she'll write for the Boston Globe through the Kaiser Family Foundation health reporting internship.

© 2012 Helen Shen