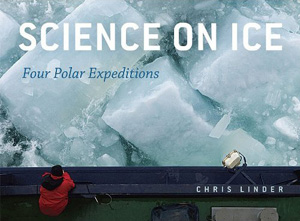

SciCom graduates Helen Fields and Hugh Powell have written chapters for Science on Ice, a chronicle of four polar science expeditions by acclaimed photographer Chris Linder. The book will be published by University of Chicago Press in December 2011.

The book documents scientific journeys to the Arctic and Antarctic regions between 2007 and 2009, during the two-year-long International Polar Year. Linder, an oceanographer at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), teamed with science writers to document the research trips on a series of websites hosted by WHOI. The writers prepared daily dispatches from the ice to accompany slideshows photographed by Linder.

Science on Ice offers highlights of four expeditions: among a teeming colony of Adélie penguins in Antarctica; through the icy waters of the Bering Sea in spring; beneath the pack ice of the eastern Arctic Ocean; and over the lake-studded surface of the Greenland Ice Sheet. Powell and Fields worked as embedded science journalists on the first and second of those expeditions, respectively.

Powell, a 2005 SciCom graduate, wrote a chapter focusing on the Adélie penguin research of David Ainley, who has studied at Ross Island since the 1960s. "Everybody thinks of Adélie penguins as adorable knee-high bumblers, but they actually are among the most defiantly rugged and determined animals on the planet," Powell says. The colonies visited by the team, including one containing a half-million penguins, are two of the southernmost breeding locales for any animal. Ainley and his colleagues are learning how these ten-pound birds manage to raise young in some of the harshest conditions in the world—and about what their survival through epoch after epoch of changing climate can teach us.

Powell's journey is recounted on this expedition page. He recalls some highlights: "We cooked dinner each night with the scientists and followed them around asking questions all day. They showed us that you can tell a young-adult penguin from a veteran just by how nervous it looks, and described how to build a penguin nest using only pebbles. We watched South Polar skuas steal penguin chicks right out of a nest and saw leopard seals skin adult penguins with their teeth. And we saw the scientists' ingenious weighbridge—a kind of penguin EZ-Pass toll booth—and their time-depth recorders, which allow them to know where penguins go and how deep they dive."

Powell rejoined Linder last winter on an Antarctic icebreaker to study the marine food chain, from dissolved iron up to creatures nearly visible without a microscope. Their dispatches and photos from that journey are posted at this site.

"Back before Santa Cruz, when I used to lie in bed and dream about what my life as a famous science writer would be like, this is what I was dreaming," says Powell, a science writer at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. "I guess there's some value in naïveté after all."

Fields, who completed the SciCom program in 2003, joined Linder in spring 2009 for a six-week research voyage on an icebreaker in the Bering Sea. About 40 other scientists and 80 crew members were on board, part of a major multiyear effort to understand the Bering Sea ecosystem. In particular, the scientists were hoping to catch an early spring event: the sudden burst of algae growth that happens as the ice melts and exposes the water to the sun for the first time in months.

The daily reports from Fields appear on this expedition page. She shares these thoughts about the trip: "Chris knows a lot about the science, and I would occasionally point out things he could photograph. I helped in other ways, too. There's a picture in the book of some copepods glowing blue as they swim around a sort of mesh sieve. While Chris shot the pictures, I had to hold the sieve tight against the corner of a sink in a cold room. He was taking photos with a long exposure, so I couldn't wiggle or shake. But to get the copepods to light up, you have to agitate them by dousing them with ice-cold seawater. Remember, my hand was right there. It was a chilly experience."

Fields, a former reporter for National Geographic and now a freelance journalist based in Washington, D.C., says the expedition was one of her most memorable assignments. "I absolutely fell in love with sea ice," she says. "It's just amazing. It's different all the time. Sometimes it's so thick the ship has to back and ram just to get through, and sometimes it's so thin it looks like water—until you notice the seagulls standing on it. It constantly changes as the ship goes through it. Thin ice cracks, then the flat pieces slide over each other. Thick ice breaks up and tumbles past the ship in chunks. I think I could watch it all day. I felt incredibly lucky to be able to go out and see these things."

Science on Ice is now available for preordering through Amazon.com.